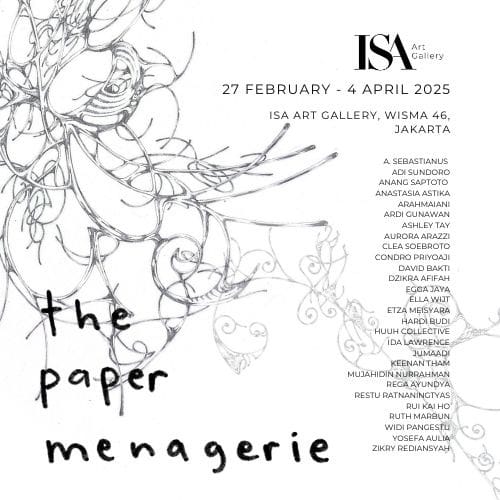

The Paper Menagerie

“She turned the paper over and folded it again. She pleated, packed, tucked, rolled, and twisted until the paper disappeared between her cupped hands. Then she lifted the folded-up paper packet to her mouth and blew into it like a balloon….

Mom’s breath was special. She breathed into her paper animals so that they shared her breath, and thus moved with her life.”

The Paper Menagerie – Ken Liu

When we think about paper, there is an inherent simplicity and raw tactility that defines the medium. It possesses a fluidity—in a sense like how water can fit into different parts of a vessel. Yet, when folded multiple times, it takes on a rigidity, almost stone-like in quality. Universally, the paper as a medium has been around for centuries. The first known paper artwork in the world is attributed to Chinese papermaking, which began during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). Paper, as we know it today, was invented by Ts’ai Lun, a Chinese court official around 105 CE in China. While paper was initially used for writing and documentation, it eventually became a medium for art.

Early forms of paper in Southeast Asia such as daluang in Java and saa paper in Thailand (mulberry bark), were crafted from tree bark and other natural fibers. These materials were used for religious texts, administrative records, and other artistic expression. Buddhist manuscripts in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Thailand were often inscribed on palm leaves or handmade paper, while Javanese and Balinese communities developed unique paper-based script traditions. This tradition was particularly notable in Javanese and Balinese literary culture, where ancient texts such as Babad Tanah Jawi and Serat Centhini were recorded on handmade materials before the arrival of European-imported paper in the colonial period.

This versatility and the way that paper can hold both the history and emotions is not just merely political, but it is also universally personal. This sense was captured in a short story by Ken Liu—the Paper Menagerie. As the title suggested ‘menagerie’ here indicates of ‘strange or diverse collection of people or things’. Here, we read how the protagonist’s mother breathes life into the paper origami that she created. Creating a menagerie of paper origamis that accompany the protagonist’s coming of age and different walk paths. As the story unfolds, the protagonist learns of his mother’s harrowing past—sold from Hong Kong to marry his father in the United States—and grapples with the sense of displacement he feels as a child of two worlds. The origami figures, become an anchor for both memory and emotion, bridging the protagonist’s fractured sense of identity and his relationship with his mother.

Paper had become such a crucial part in the story, the nooks, the pleats and the crannies on the paper mapped out an entire memory and the emotional weight that we created. We associated paper with something that is quite mundane, it is almost became a repository of our lived experiences; receipts when we buy something at the grocery store, flyers from the nearby warteg, scribbles on our office post-it notes. Despite its ubiquity, we often overlook its presence and the ways in which it quietly anchors our lives, recording fragments of our routines and interactions.

When the mother left a handwritten letter to the protagonist, inscribed in Chinese characters, the moment carries a painful irony—there is something so poignant about how the protagonist kind of have to asked around to read his own mother’s handwriting. In this quiet moment, the loss of language as a severance from one's origins, a rupture in the continuum of memory and identity. The letter, written on something as delicate and impermanent as paper, embodies the fragility of heritage—how easily it can be forgotten, misplaced, or rendered unreadable by time and distance.

Yet, paper also serves as an archive of what lingers. It holds ink, absorbs meaning, and carries the weight of histories too easily erased. The protagonist’s struggle to understand his mother’s words mirrors a broader, universal tension—how many of us have found ourselves unable to decipher the languages of our ancestors, estranged from the very histories that formed us? This disconnection is not merely linguistic but broadens to the existential, speaking to the erasure that can occur when cultures are marginalized, displaced, or forcibly assimilated. And yet, within this act of reading—of searching for understanding—there remains the possibility of reconnection. The act of translation, both literal and metaphorical, becomes an effort to recover lost narratives, to bridge the space between past and present. Perhaps this is why paper has remained a favored medium for both resistance and remembrance: in its quiet unassuming nature, it bears witness, absorbs longing, and, like the letter left behind, waits to be read, understood, and remembered.

-

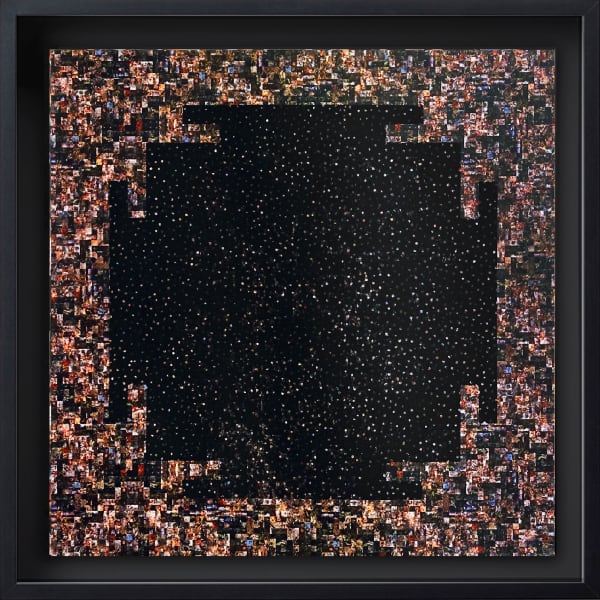

Adi Sundoro, Persatuan Mental Tempe #1, 2022

Adi Sundoro, Persatuan Mental Tempe #1, 2022 -

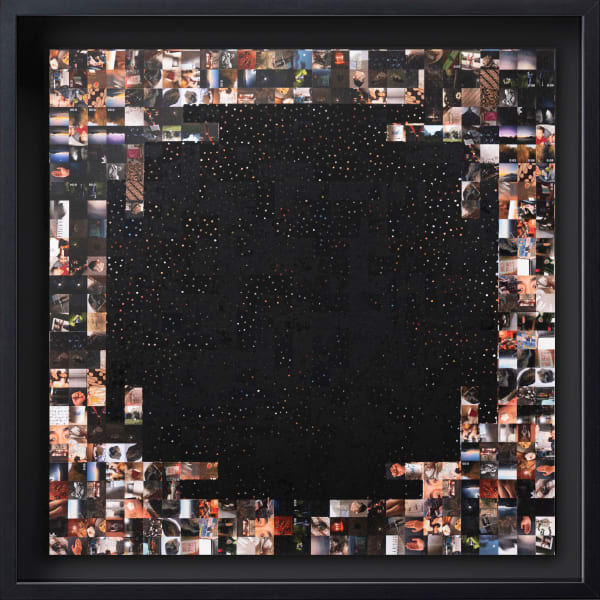

Adi Sundoro, Persatuan Mental Tempe #2, 2022

Adi Sundoro, Persatuan Mental Tempe #2, 2022 -

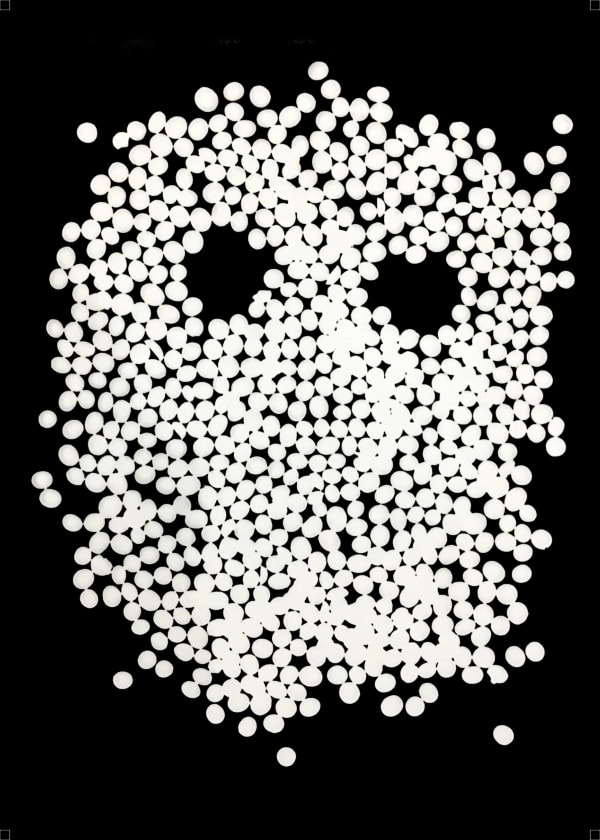

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Coconut Seeds in Photogram, 2018

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Coconut Seeds in Photogram, 2018 -

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Goat Manure in Cyanotype, 2023

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Goat Manure in Cyanotype, 2023 -

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Grated Coconut in Lumen Print, 2018

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Grated Coconut in Lumen Print, 2018 -

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Soybean Seeds in Photogram, 2018

Anang Saptoto, Ecological Faces Series: Soybean Seeds in Photogram, 2018 -

Arahmaiani, Suara Alam 1, 2024

Arahmaiani, Suara Alam 1, 2024 -

Arahmaiani, Suara Alam 4, 2024

Arahmaiani, Suara Alam 4, 2024 -

Arahmaiani, Suara Alam 2, 2024

Arahmaiani, Suara Alam 2, 2024 -

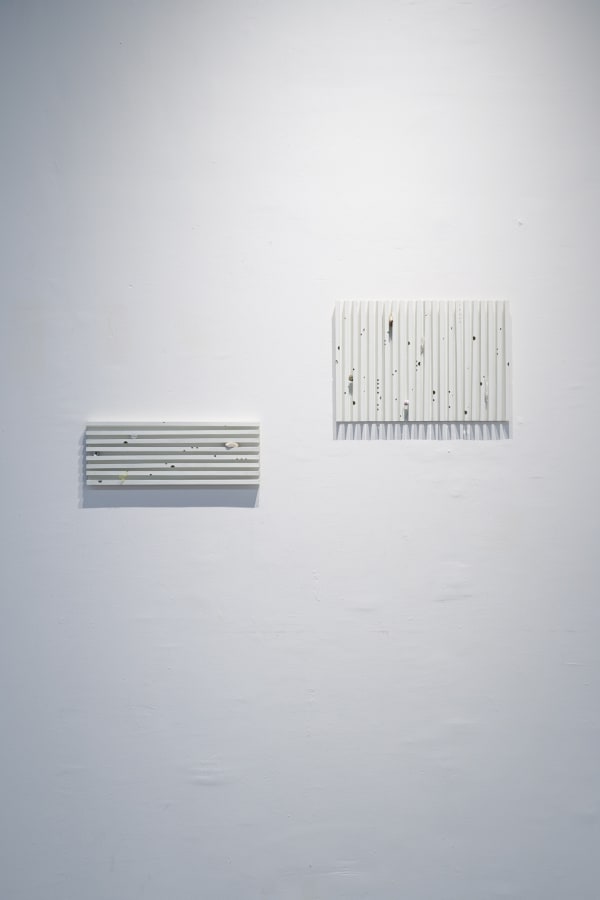

Ardi Gunawan, The wall is calling #5, 2017

Ardi Gunawan, The wall is calling #5, 2017 -

Ardi Gunawan, The wall is calling #10, 2017

Ardi Gunawan, The wall is calling #10, 2017 -

Ashley Tay, Coma, 2023

Ashley Tay, Coma, 2023 -

Ashley Tay, Galore, 2023

Ashley Tay, Galore, 2023 -

Ashley Tay, Unearth, 2023

Ashley Tay, Unearth, 2023 -

Clea Soebroto, Tulang Rusuk (Ribs), 2023

Clea Soebroto, Tulang Rusuk (Ribs), 2023 -

Clea Soebroto, Tulang Rusuk (Ribs), 2023

Clea Soebroto, Tulang Rusuk (Ribs), 2023 -

Dzikra Afifah, Seamus, 2022

Dzikra Afifah, Seamus, 2022 -

Dzikra Afifah, Happier than Ever, 2022

Dzikra Afifah, Happier than Ever, 2022 -

Iwan Effendi, Portrait 1, 2020 - 2025

Iwan Effendi, Portrait 1, 2020 - 2025 -

Iwan Effendi, Portrait 2, 2020 - 2025

Iwan Effendi, Portrait 2, 2020 - 2025 -

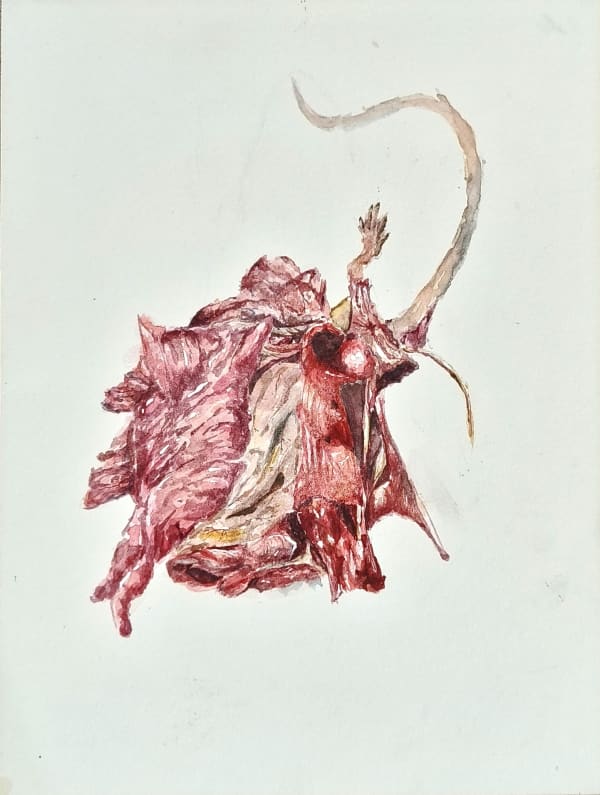

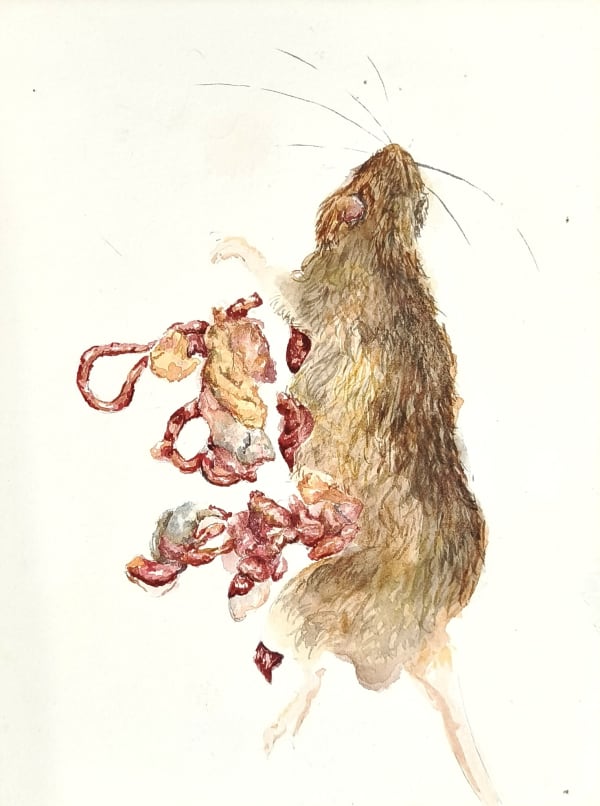

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 1, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 1, 2023 -

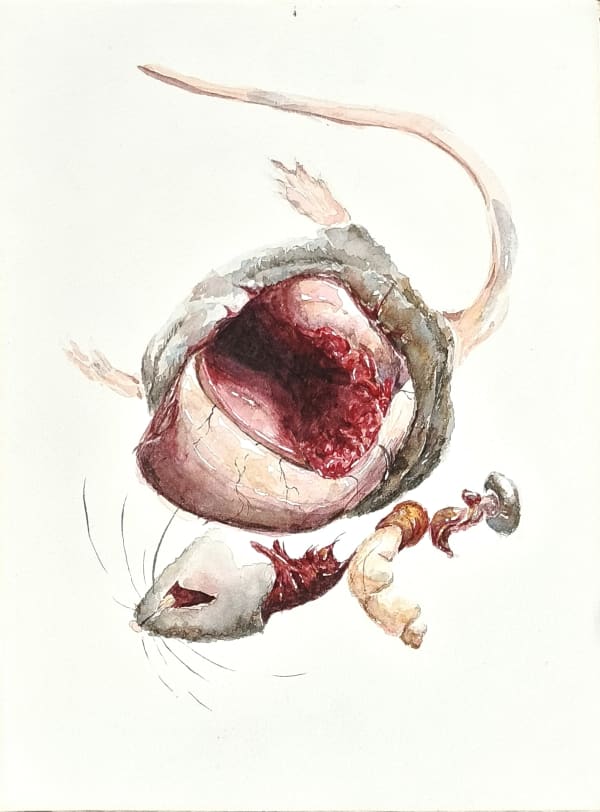

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 2, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 2, 2023 -

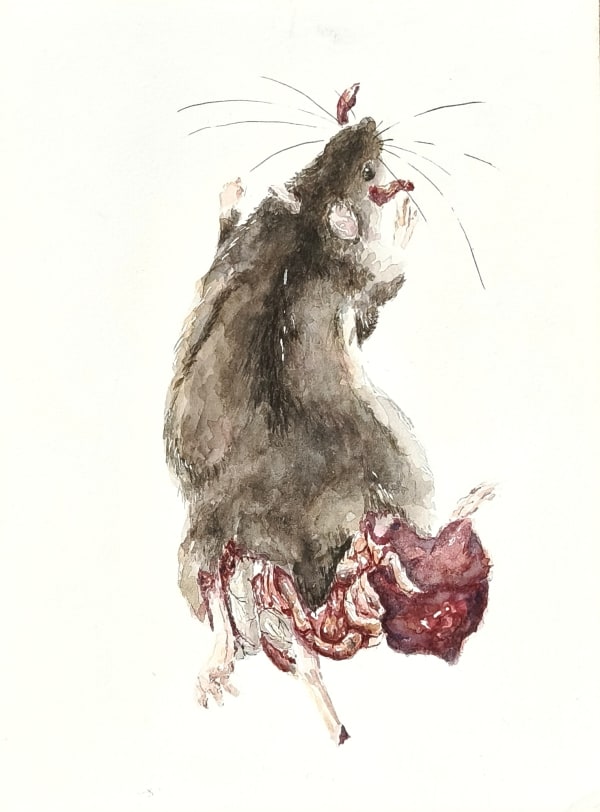

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 3, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 3, 2023 -

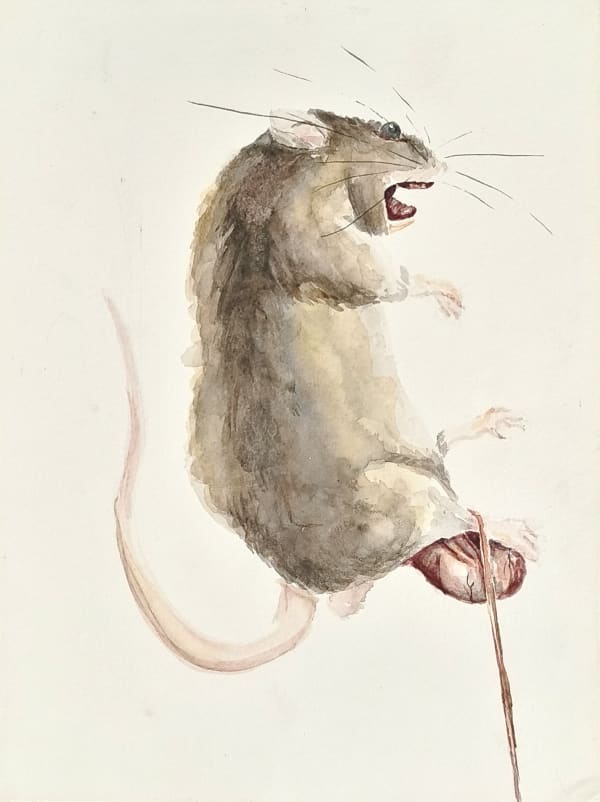

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 4, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 4, 2023 -

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 5, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 5, 2023 -

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 6, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 6, 2023 -

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 7, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 7, 2023 -

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 8, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 8, 2023 -

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 9, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 9, 2023 -

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 10, 2023

Keenan Tham, Rat Race 10, 2023 -

Rui Kai Ho, Round Animals #1 (Sea Doggo), 2024

Rui Kai Ho, Round Animals #1 (Sea Doggo), 2024 -

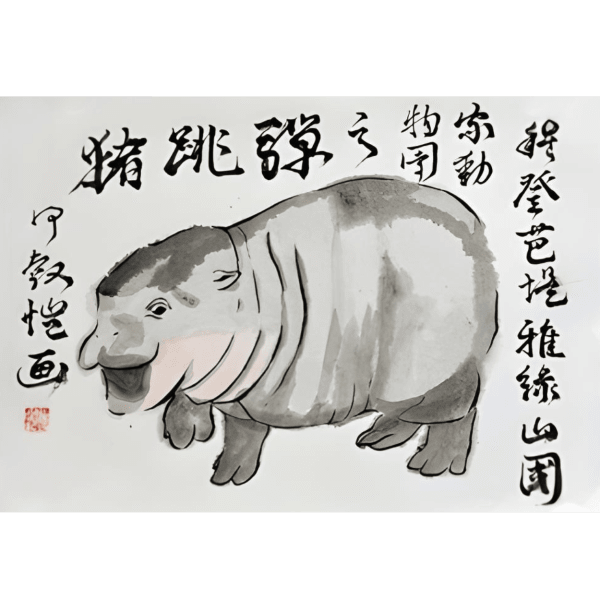

Rui Kai Ho, Round Animal #2 (Moo Deng), 2024

Rui Kai Ho, Round Animal #2 (Moo Deng), 2024 -

Rui Kai Ho, Round Animal #3 (Pesto), 2024

Rui Kai Ho, Round Animal #3 (Pesto), 2024 -

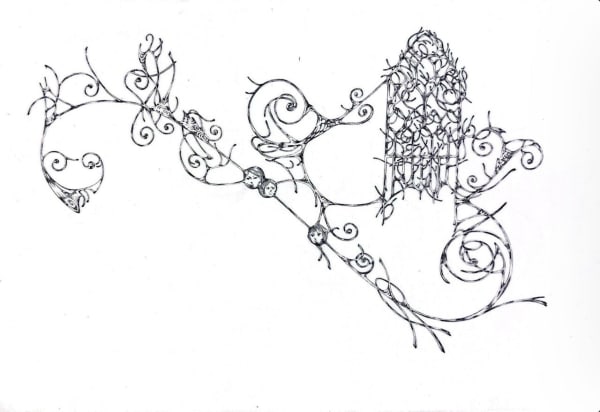

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #1, 2025

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #1, 2025 -

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #2, 2025

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #2, 2025 -

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #3, 2025

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #3, 2025 -

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #4, 2025

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #4, 2025 -

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #5, 2025

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #5, 2025 -

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #6, 2025

Zikry Rediansyah, Halaman Terakhir Dalam Catatan #6, 2025 -

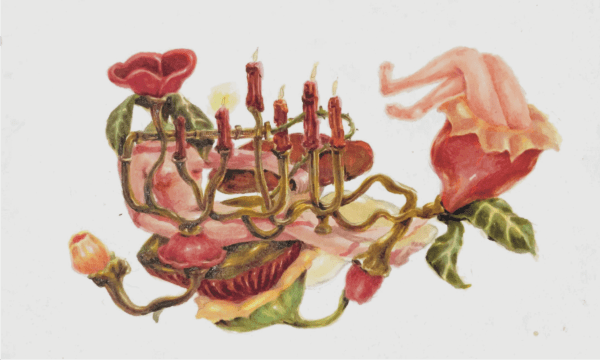

Anastasia Astika, Petal Party I, 2025

Anastasia Astika, Petal Party I, 2025 -

Anastasia Astika, Petal Party II, 2025

Anastasia Astika, Petal Party II, 2025 -

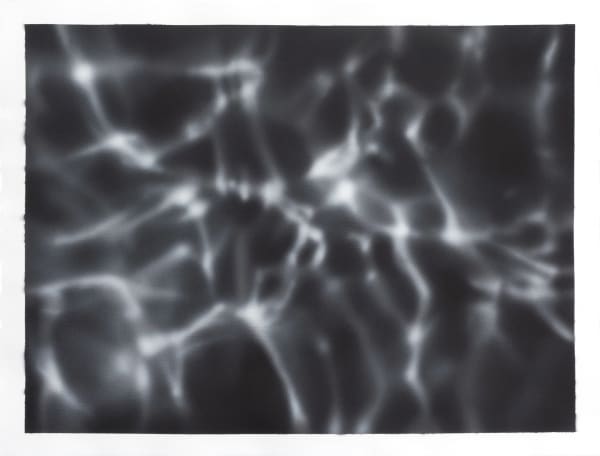

Condro Priyoaji, Reflection Eternal, 2025

Condro Priyoaji, Reflection Eternal, 2025 -

Ida Lawrence, Kind(s) , 2019

Ida Lawrence, Kind(s) , 2019 -

Ida Lawrence, Wylie’s with Huw , 2019

Ida Lawrence, Wylie’s with Huw , 2019 -

Yosefa Aulia, Pale Pink, 2024

Yosefa Aulia, Pale Pink, 2024 -

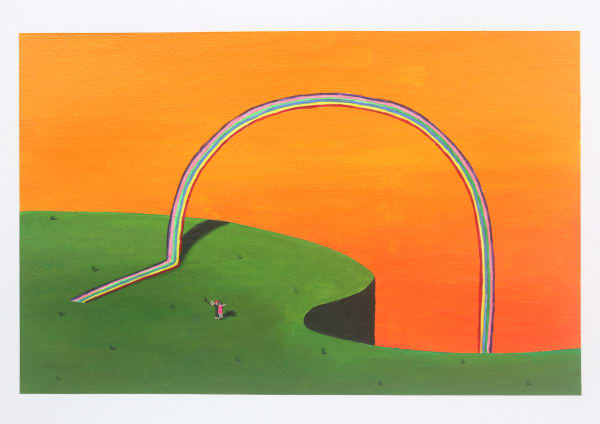

Yosefa Aulia, Out of Bound, 2024

Yosefa Aulia, Out of Bound, 2024 -

Yosefa Aulia, Detached , 2024

Yosefa Aulia, Detached , 2024 -

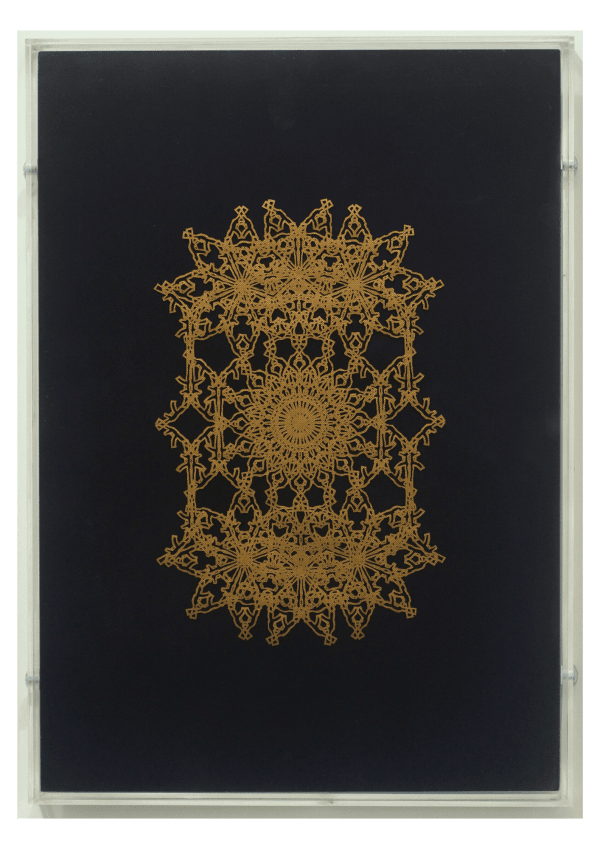

Alexander Sebastianus, Sunyata #01, 2025

Alexander Sebastianus, Sunyata #01, 2025 -

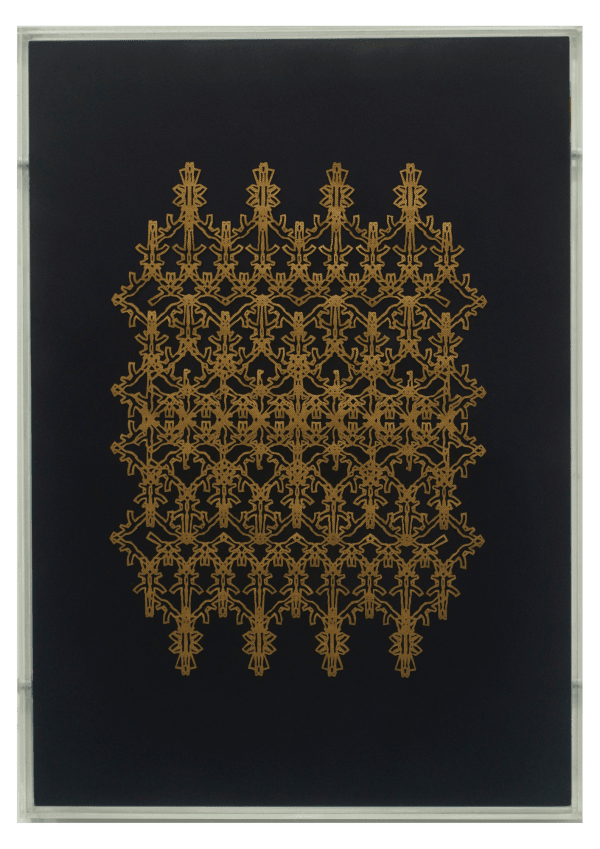

Alexander Sebastianus, Sunyata #02, 2025

Alexander Sebastianus, Sunyata #02, 2025 -

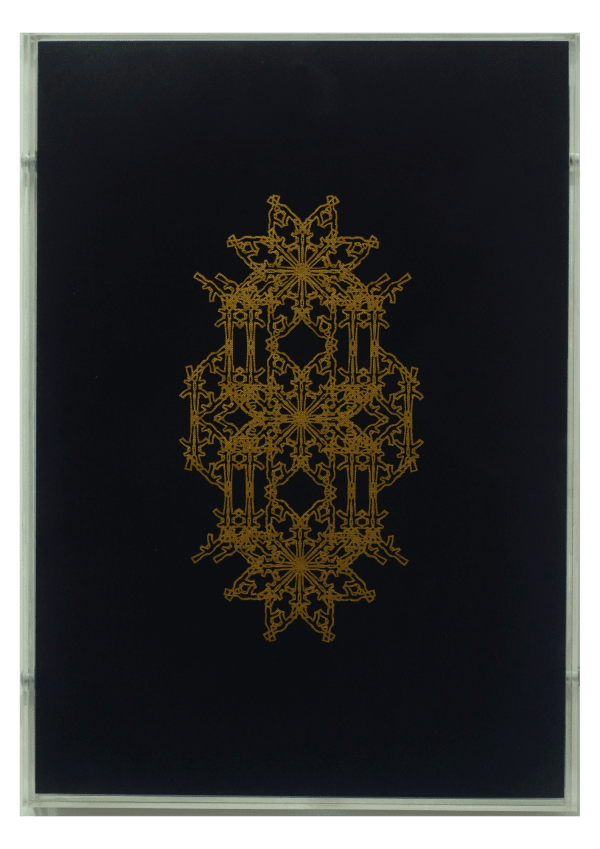

Alexander Sebastianus, Purnatva #01, 2025

Alexander Sebastianus, Purnatva #01, 2025 -

Alexander Sebastianus, Purnatva #02, 2025

Alexander Sebastianus, Purnatva #02, 2025 -

Ella Wijt, The Wives of the Nightfall, 2025

Ella Wijt, The Wives of the Nightfall, 2025 -

Ella Wijt, Spring Rising, 2025

Ella Wijt, Spring Rising, 2025 -

Ella Wijt, Portal, 2025

Ella Wijt, Portal, 2025 -

Hardijanto Budiman, Dance Like There is No Tomorrow , 2023

Hardijanto Budiman, Dance Like There is No Tomorrow , 2023 -

Hardijanto Budiman, Our Blues , 2020

Hardijanto Budiman, Our Blues , 2020 -

HUUH Collective, Unpacking The Home, 2024

HUUH Collective, Unpacking The Home, 2024 -

Rega Ayundya Putri, Awan(g), 2016-2024

Rega Ayundya Putri, Awan(g), 2016-2024 -

Rega Ayundya Putri, Lengang, 2016

Rega Ayundya Putri, Lengang, 2016 -

Rega Ayundya Putri, Surut, 2022

Rega Ayundya Putri, Surut, 2022 -

Restu Ratnaningtyas, Bersabar, 2025

Restu Ratnaningtyas, Bersabar, 2025 -

Aurora Arazzi, The sound under my shoe #1, 2025

Aurora Arazzi, The sound under my shoe #1, 2025 -

Aurora Arazzi, The sound under my shoe #2, 2025

Aurora Arazzi, The sound under my shoe #2, 2025 -

Egga Jaya Prasetya, Tanggah:stepped dome, 2025

Egga Jaya Prasetya, Tanggah:stepped dome, 2025 -

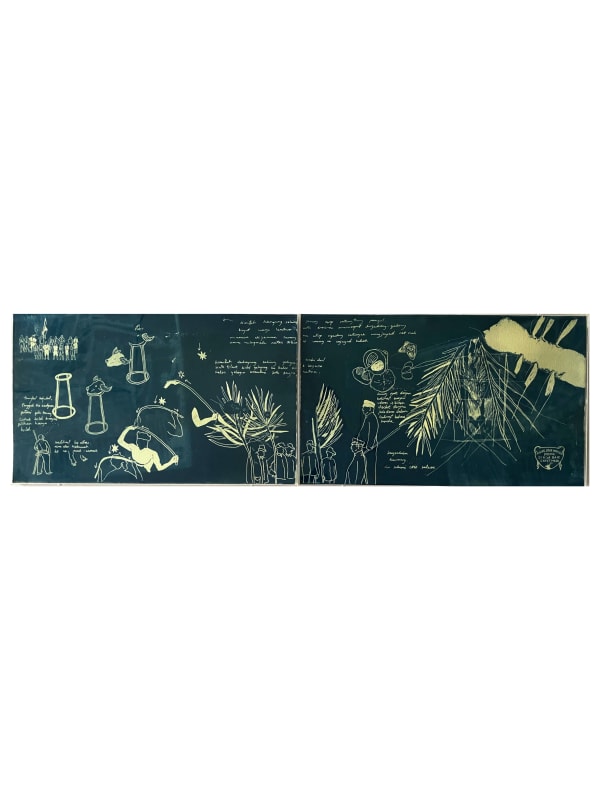

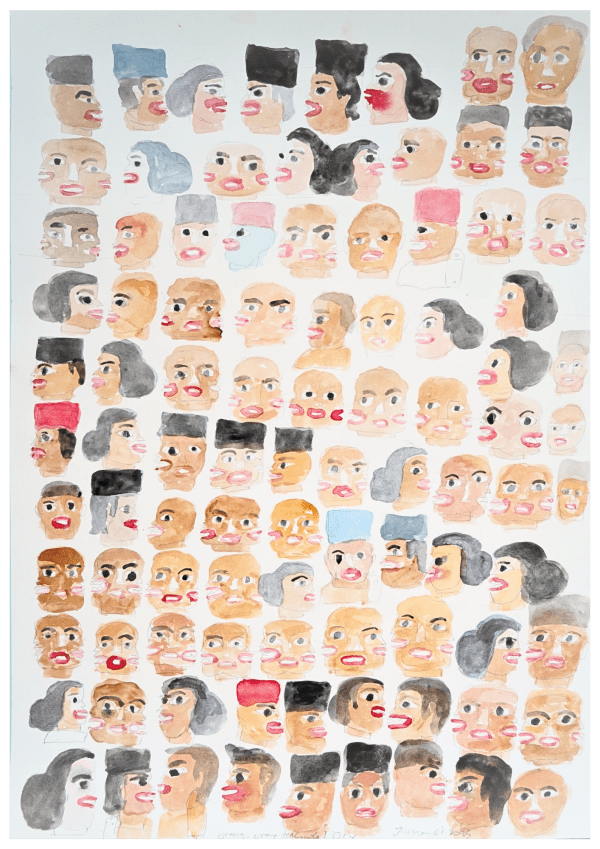

Jumaadi, Orang-Orang Tercinta 1 - DIY, 2025

Jumaadi, Orang-Orang Tercinta 1 - DIY, 2025 -

Jumaadi, Orang-Orang Tercinta 2 - Bali, 2025

Jumaadi, Orang-Orang Tercinta 2 - Bali, 2025 -

Jumaadi, Orang-Orang Tercinta 3, 2025

Jumaadi, Orang-Orang Tercinta 3, 2025 -

Widi Pangestu Soegiono, Contour, 2025

Widi Pangestu Soegiono, Contour, 2025 -

Widi Pangestu Soegiono, Mossy, 2025

Widi Pangestu Soegiono, Mossy, 2025 -

Widi Pangestu Soegiono, Raintree, 2025

Widi Pangestu Soegiono, Raintree, 2025 -

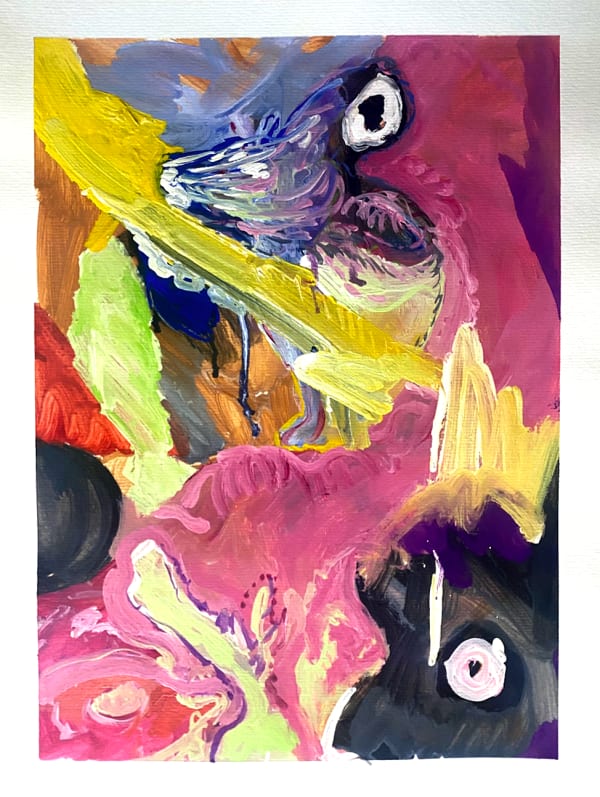

Ruth Marbun, 1/Bersuar, 2025

Ruth Marbun, 1/Bersuar, 2025 -

Ruth Marbun, 2/Bersuara, 2025

Ruth Marbun, 2/Bersuara, 2025 -

Ruth Marbun, 3/Bersuaka, 2025

Ruth Marbun, 3/Bersuaka, 2025 -

Mujahidin Nurrahman, Where does all this beauty come from #1, 2025

Mujahidin Nurrahman, Where does all this beauty come from #1, 2025 -

Mujahidin Nurrahman, Where does all this beauty come from #2, 2025

Mujahidin Nurrahman, Where does all this beauty come from #2, 2025 -

Mujahidin Nurrahman, Where does all this beauty come from #3, 2025

Mujahidin Nurrahman, Where does all this beauty come from #3, 2025 -

Etza Meisyara, Arkala, 2022

Etza Meisyara, Arkala, 2022 -

David Bakti, Puisi Amplas No. 02, 2024

David Bakti, Puisi Amplas No. 02, 2024 -

David Bakti, Puisi Amplas No. 03, 2025

David Bakti, Puisi Amplas No. 03, 2025